Judaism Is Not Zionism

The world must understand this truth: The Zionist government does not act in our name

Jewish People:

3,000 Years

A religious collective founded upon receiving GD’s holy Torah at Mount Sinai, in the desert, without any shared land. (Deuteronomy 27:9).

Zionism:

150 Years

A political movement that co-opted Jewish identity, transforming our sacred faith into earthly nationalism and pursuit of political ambitions.

Our Way:

Torah Law

We follow God’s commandments, live in peace with our neighbors, and uphold the core Torah values of kindness and compassion toward all.

Their Way:

Force

Zionists rely on military power, nationalist ideology, and actions that contradict fundamental Torah principles.

When Zionists Act in Violence - That's NOT Judaism

Every military action, every oppressive policy, every violation of human rights by the Zionist state is a violation of Torah law. They do not represent Jews. They do not represent Judaism.

About Torah Jews

Torah Jews was founded more than twenty years ago by Rabbi Moshe Dovid Katz, at the request and with the encouragement of the Satmar community, to serve as an organized voice articulating the Torah-based opposition to Zionism. The organization is also known as נטרונא (Natruna).

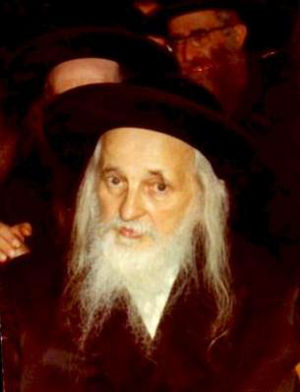

Our Guide & Mentor:

Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum zt"l (1887-1979)

"We must have self sacrifice to let the nations of the world know that these wicked men (Zionists) are not the representatives of the Jewish people, and that observant Jews have no connection with them, it would be one of the biggest Mitzvos to do so!"

(Kinus Haklali, 1961, printed in Divrei Yoel Naso p. 128-9)

Real-Time Clarifications

When Israel’s actions make headlines, we’re here to tell the world: That is not Judaism. Follow us for real-time responses to current events on social media.

Torah Jews X feed

Speaking Truth to the World

Stay informed about our efforts to distinguish true Judaism from nationalist Zionism.

What the World Needs to Know

Common misconceptions about Jews and Zionism:

The Three Oaths:

Why Jews Cannot Have a State

Understanding the sacred agreement between G-d and the Jewish people

"G-d made the Jewish people swear not to return to Israel by force, not to rebel against the nations, and not to hasten the redemption."

Wisdom Across Generations

Great Torah minds united in understanding

"It is a serious danger to the Jewish people if they point to those who do not keep the Torah and deny Hashem and call them the leaders of the Jewish people. All the nations are thereby misled to think that they speak in the name of Jewry, and thus they are transformed into anti-Semites." (Kinus Haklali, 1961, printed in Divrei Yoel Naso p. 128-9)

"The Torah united all the individual Jews and made them a nation, and therefore even after they were distanced from their land, they are a nation, not primarily because of their past, nor because of their future, but because they are the bearers of an eternal tradition, a people that fulfills its covenant with Hashem." - Horeb

"The Jewish people have suffered many plagues – the Sadducees, Karaites, Hellenisers, Shabbesai Zvi, Haskalah, Reform and many others. But the strongest of them all is Zionism, because its heresy focuses on the center of Judaism.” (Mishkenos Haro’im p. 269)

Help Us Set the Record Straight

The world must hear it with unshakable truth: Zionism is not Judaism.

Share the Truth

Help us reach more people with the message that millions of Jews oppose Zionism on religious grounds.

📱 Share on Social Media

📧 Email to Friends

Media & Press

Journalists and media: Contact us for statements when covering Zionist actions. We provide the Torah perspective.

Educational Resources

Download materials explaining the difference between Judaism and Zionism for schools, libraries, and communities.

Remember This Simple Truth:

When you see violence committed by the Zionist state,

know that Orthodox Jews worldwide say:

"NOT IN OUR NAME"

Stay Informed

Receive weekly Torah insights and community updates